Trigeminal Neuralgia vs TMJ Symptom Checker

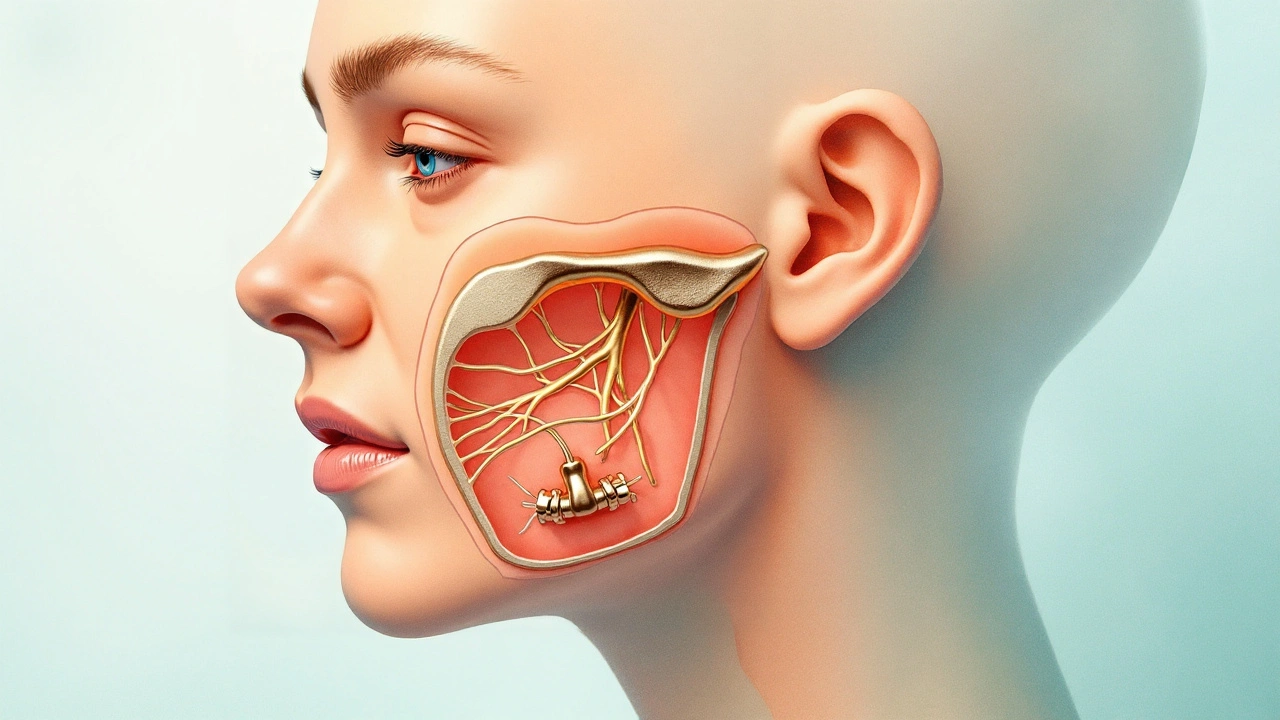

Trigeminal Neuralgia is a neuropathic facial pain condition caused by irritation or compression of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), characterized by sudden, electric‑shock‑like bursts that can last seconds to minutes. It most often affects people over 50 and is considered one of the most painful disorders known to medicine.

Temporomandibular Joint Disorder (often shortened to TMJ disorder) is a musculoskeletal condition involving the jaw joint, surrounding muscles, and related structures. Symptoms range from clicking or popping noises to chronic ache that radiates to the ear, neck, and even the shoulders.

When patients report both a stabbing facial pain and jaw discomfort, clinicians frequently wonder: are these two separate problems, or do they share a hidden link? Below we unpack the anatomy, the overlapping triggers, and the practical steps you can take to get relief.

Understanding Trigeminal Neuralgia (TN)

The trigeminal nerve splits into three branches: the ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3). Mandibular branch is the only branch that also supplies the muscles of mastication, the same group that moves the jaw during chewing. Because of this dual role, any irritation that affects V3 can send pain signals that feel like they’re coming from the jaw, teeth, or ear.

Common causes of TN include:

- Vascular compression - an artery or vein pressing against the nerve root.

- Multiple sclerosis - demyelination of the trigeminal pathway.

- Dental procedures - nerve trauma during extractions or implants.

Diagnosis often relies on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with high‑resolution sequences that can visualize the offending vessel. A clinical test called the “trigger zone” assessment helps confirm the diagnosis by reproducing the shock‑like pain with light touch.

Understanding TMJ Disorders

TMJ disorder covers a spectrum of issues, from simple joint inflammation (arthrosis) to complex muscle pain (myofascial pain syndrome). Key contributors include:

- Bruxism - grinding or clenching teeth, often linked to stress.

- Poor occlusion - misaligned bite that forces uneven pressure on the joint.

- Arthritic changes - degenerative wear that narrows the joint space.

Patients may notice a dull ache that worsens with wide yawning, chewing gum, or speaking for long periods. Unlike TN’s quick jolts, TMJ pain tends to be persistent and may radiate to the neck.

Why the Two Conditions Often Appear Together

The overlap stems from three main pathways:

- Shared Nerve Pathway - The mandibular branch (V3) supplies both the joint capsule and the muscles that move the jaw. Any irritation of V3 can manifest as both neuralgic spikes and joint‑related soreness.

- Muscle Tightness and Nerve Irritation - Chronic bruxism or jaw clenching creates muscle hypertrophy. Tight muscles can compress the trigeminal nerve near its exit from the skull, mimicking a vascular compression.

- Central Sensitization - Persistent pain from TMJ can sensitize the central nervous system, lowering the threshold for trigeminal pain episodes. Conversely, repeated TN attacks can increase muscle tension, feeding back into TMJ stress.

Understanding these connections helps clinicians treat the root cause rather than just the symptoms.

Diagnostic Overlap: Spotting the Twin Trouble

Because the symptoms can mask each other, a thorough evaluation is essential. Here’s a practical checklist:

- Document exact pain quality: sharp, electric shocks vs. steady, throbbing ache.

- Map pain locations: V2/V3 skin distribution versus joint line near the ear.

- Assess trigger factors: light touch on the cheek (TN) vs. chewing or yawning (TMJ).

- Order imaging: MRI for nerve compression, panoramic X‑ray or CBCT for joint structure.

- Consider a diagnostic block: a temporary anesthetic near the mandibular nerve can differentiate neural vs. muscular origin.

When both scans show vascular contact on the nerve and signs of joint degeneration, you’ve likely got a double‑dose problem.

Integrated Treatment Strategies

Addressing the two conditions together yields better outcomes. Below is a tiered approach that many specialists follow.

First‑Line Conservative Care

Start with low‑risk interventions that target both pain sources:

- Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections into the masseter and temporalis muscles reduce clenching and can also lessen nerve irritation.

- Custom night‑guard to limit bruxism, often fabricated after a dental impression.

- Physical therapy focusing on jaw mobilization and cervical spine alignment - helps loosen tight muscles that may be pinching the trigeminal nerve.

- Pain‑modulating medications: carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine for TN; NSAIDs or muscle relaxants for TMJ.

Interventional Options

If symptoms persist, consider procedures that directly address the underlying cause:

- Microvascular decompression (MVD) surgery - moves the offending artery away from the trigeminal root. Success rates exceed 80% for classic TN.

- Arthrocentesis or arthroscopy of the TMJ - flushes out inflammatory fluid and can release adhesions.

- Radiofrequency rhizotomy - precise lesioning of the mandibular branch to block pain signals, reserved for refractory TN.

Long‑Term Maintenance

Even after successful surgery, lifestyle tweaks keep the pain at bay:

- Stress‑management techniques (mindfulness, yoga) cut down on bruxism.

- Regular dental check‑ups to monitor bite changes.

- Gentle jaw exercises prescribed by a physiotherapist to maintain joint flexibility.

Comparison of Trigeminal Neuralgia and TMJ Disorder

| Aspect | Trigeminal Neuralgia | TMJ Disorder | Common Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain type | Sharp, electric‑shock bursts | Dull, aching, throbbing | Both can radiate to ear and cheek |

| Trigger zones | Light touch, cold wind, chewing (brief) | Wide mouth opening, chewing gum, stress | Chewing can exacerbate both |

| Primary nerve | Trigeminal (V3 branch) | Mandibular branch (V3) + joint receptors | Shared V3 involvement |

| Diagnostic test | MRI for vascular compression | CBCT or MRI for joint morphology | Imaging often ordered together |

| First‑line meds | Carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine | NSAIDs, muscle relaxants | Botox can help both |

Related Concepts and Next Steps in the Health Knowledge Cluster

This article sits within the broader Neuropathic Pain cluster, which also includes conditions like post‑herpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy. Narrower topics worth exploring next are "Microvascular Decompression Techniques" and "Conservative TMJ Therapies". Conversely, the broader landscape covers "Chronic Pain Management" and "Pain Neuroscience Education".

When to Seek Specialist Care

If you experience any of the following, book an appointment with a neurologist or oral‑maxillofacial surgeon promptly:

- Sudden, severe facial pain that disrupts daily activities.

- Persistent jaw pain that worsens with biting or yawning.

- Any loss of sensation, facial weakness, or difficulty opening the mouth.

- Failure of over‑the‑counter pain relievers after two weeks.

Early intervention not only eases suffering but can prevent secondary changes like muscle atrophy or anxiety‑driven bruxism.

Quick Take‑aways

- The mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve links TN and TMJ intimately.

- Shared triggers include chewing, stress, and muscle tightness.

- Comprehensive diagnosis uses both MRI (for nerve) and joint imaging.

- Treatment works best when it targets both nerve irritation and joint dysfunction.

- Long‑term success hinges on stress management, dental monitoring, and regular physiotherapy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can trigeminal neuralgia cause jaw clicking?

Jaw clicking is usually a sign of joint involvement rather than pure nerve irritation. However, severe TN attacks can make the muscles around the jaw tense, which in turn may accentuate an existing click. Treating the muscle tension often reduces both symptoms.

Is a night‑guard enough to treat both conditions?

A night‑guard helps control bruxism and eases TMJ strain, but it does not address the nerve compression that drives TN. Most patients benefit from a night‑guard plus medication or Botox to manage the neural component.

What medications work for both TN and TMJ pain?

Carbamazepine is the gold standard for TN but offers little relief for TMJ. Conversely, NSAIDs help TMJ but not TN. Botox injections bridge the gap by reducing muscle spasm (TMJ) and dampening nerve firing (TN).

How successful is microvascular decompression for patients who also have TMJ disorder?

MVD relieves the neuralgic component in over 80% of classic cases. When TMJ symptoms coexist, patients usually notice a drop in jaw‑related tension because the nerve is no longer irritated, but they may still need physiotherapy or a night‑guard for joint health.

Can stress management alone improve both conditions?

Stress reduction lowers bruxism, which eases TMJ strain, and it also reduces muscle tension that can aggravate nerve compression. While it often helps, most patients still need at least one medical or dental intervention for full relief.

10 Comments

Leigh Guerra-Paz

I’ve been dealing with this exact combo for years-TN spikes that feel like my face is being stabbed, AND my jaw feels like it’s full of gravel. I didn’t realize they could feed each other until my neurologist mentioned central sensitization. It’s wild how one pain can make the other worse. Botox was a game-changer for me-not just for the clenching, but the electric shocks got less frequent. I still wear my night guard religiously, and honestly? I think it saved my teeth and my sanity. 🙏

shelly roche

So many people think it’s either ‘just TMJ’ or ‘just nerve pain’-but this post nails it. The shared V3 pathway is everything. I had both, and my dentist missed the TN part for over a year because my pain felt ‘muscular.’ MRI showed a rogue artery hugging my nerve like it owed it money. Once we treated both, my life changed. Don’t let anyone tell you it’s ‘all in your head.’ It’s in your nerves-and your jaw-and they’re talking to each other.

Nirmal Jaysval

bruh why u guys overcomplicate this? its just stress. stop clenching. wear a guard. done. no need for botox or mri or whatever. my cousin had this and he just chillaxed and now hes fine. u need less meds, more zen.

Emily Rose

Nirmal, I get where you’re coming from-but dismissing this as ‘just stress’ ignores the biological reality. Trigeminal neuralgia isn’t a mindset-it’s a damaged nerve. And if you’ve got both TN and TMJ? That’s a perfect storm. I’m a physical therapist, and I’ve seen patients who did ‘just chill’ for years and ended up with permanent muscle contractures and nerve damage. This isn’t about willpower. It’s about targeted care. You don’t ‘meditate away’ a vascular compression.

Benedict Dy

Let’s be honest: most of these ‘integrated treatment strategies’ are just expensive band-aids. Botox? Temporary. MVD? High-risk. Night guards? Only help if you actually wear them-which most don’t. The real issue? We’re treating symptoms instead of root causes. Why isn’t anyone talking about the role of chronic inflammation from diet? Or the gut-brain axis? This entire field is reactive, not proactive. And yes, I’ve read the papers. You’re welcome.

Emily Nesbit

Actually, your point about diet and inflammation is valid, Benedict. There’s emerging evidence linking systemic inflammation to trigeminal hyperexcitability. One 2022 study in *The Journal of Headache and Pain* showed elevated CRP levels in TN patients with comorbid TMJ. And yes-many of them had high-glycemic diets. It’s not the whole answer, but it’s a piece. Stop dismissing the complexity. This isn’t a one-size-fits-all condition.

John Power

Y’all are overthinking this. I had both. I started doing jaw stretches every morning, cut out caffeine, and used a cold pack on my cheek when the spikes hit. Didn’t need Botox. Didn’t need surgery. My pain dropped 70% in 3 weeks. It’s not magic-it’s consistency. If you’re stressed, breathe. If your jaw hurts, move it gently. If your face feels like it’s on fire, ice it. Sometimes the simplest stuff works. Don’t let the hype scare you into thinking you need a PhD to feel better.

Richard Elias

lol you think ice and stretches fix TN? bro your nerve is being squished by an artery. you think cold water is gonna move that? please. you’re the reason people delay real treatment. i had a friend who did your ‘simple stuff’ for 2 years. ended up with permanent numbness and a messed up bite. don’t be that guy.

Scott McKenzie

John, I love your approach! 🙌 I’m a big believer in the combo: gentle movement + ice + stress reduction. I did all that AND used a night guard-and it worked *for me*. But I also know it’s not universal. That’s why I’m grateful for this post-it shows there’s a spectrum. What helps one person might not help another. The key is listening to your body and not giving up until you find your combo. Also, Botox? Totally worth a try. It’s not forever, but it’s a reset button. 😊

Jeremy Mattocks

Let me add something practical: if you’ve got both TN and TMJ, track your pain daily. Use a simple app or even a notebook. Note what you ate, how much you slept, whether you were stressed, and whether you chomped on gum or chewed on one side. I did this for 6 months and noticed a pattern: every time I skipped my magnesium supplement, my TN flared within 24 hours-and my jaw tightened up. Turns out, magnesium helps relax both muscles AND nerves. I started taking 400mg nightly. My electric shocks went from 8/day to 1-2/week. Not a cure, but a huge win. And yes, I still wear my guard. And do my stretches. And yes, I still cry sometimes when the pain hits. But now? I feel like I’m fighting back, not just surviving.