When a company invents a new drug, medical device, or life-saving technology, they don’t just file a patent and wait. They play a high-stakes game of timing across dozens of countries. Why? Because patent expiration isn’t the same everywhere. Even though the world agreed on a 20-year standard, real-world expiration dates can vary by years depending on where you look.

The Global Standard: 20 Years from Filing

Since 1995, nearly every country that matters economically has followed the same rule: patents expire 20 years from the earliest filing date. This came from the TRIPS Agreement under the World Trade Organization. Before that, the U.S. used to give patents 17 years from the grant date-meaning a patent filed in 1980 could still be active in 1997 if it wasn’t approved until 1980. That’s why the shift to a filing-based clock was so important. It made global patent portfolios predictable.

But here’s the catch: the 20-year clock doesn’t start when you get the patent. It starts when you first file. That means if you file in the U.S. on January 1, 2020, and then file in Germany, Japan, and Brazil six months later, all those patents expire on January 1, 2040. The filing date is king.

What Happens Before You Get the Patent?

Most inventors don’t file directly in every country. They use the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). This lets them file one application that buys them time-up to 30 or 31 months-to decide where to pursue protection. During that window, they can test markets, raise funds, or tweak the invention. But the clock doesn’t stop. The 20-year term still runs from the original filing date. So if you file a PCT application on March 15, 2023, and enter the national phase in Canada on September 15, 2025, your Canadian patent still expires on March 15, 2043. The delay in national entry doesn’t extend your protection.

Some countries let you apply for extensions if you miss the deadline. Japan gives you two extra months. The U.S. lets you pay a fee for a two-month grace period. But if you wait too long? The patent is gone. No second chances.

Patent Term Adjustments: The Hidden Clock

Here’s where things get messy. The patent office can delay things. A lot. And in some countries, they have to pay for it-by giving you more time.

In the U.S., if the Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) takes too long to examine your application, you get Patent Term Adjustment (PTA). In 2022, the average patent got 558 extra days. That’s almost 1.5 years added to the clock. A patent that would’ve expired in 2037 might now last until 2038 or 2039. But this doesn’t happen everywhere. India gives no extensions, no matter how long the backlog. Australia gives extensions for unreasonable delays, but only if you ask. China and Japan now offer similar adjustments, but only for specific cases-like if the patent office took more than three years to examine.

These adjustments are why two identical patents filed on the same day can expire on different dates. One might have been reviewed quickly. The other got buried in paperwork. That’s why big pharma companies track PTA like stock prices.

Pharmaceutical Extensions: The 5-Year Bonus

Drugs take forever to get approved. Clinical trials, safety reviews, regulatory hurdles-it can take 10 years just to get from patent filing to market. That eats up half your patent life before you even start selling.

To fix this, countries like the U.S., EU, Japan, and Canada offer Patent Term Extensions (PTE) or Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). These add up to five extra years to the patent term, but only for drugs. The U.S. allows it under Section 156 of the law. The EU lets you extend by up to five years, plus six months if you do pediatric studies.

But here’s the twist: you can’t get an extension unless you apply. And you can only apply once. If you miss the deadline, you lose it. In 2023, Pfizer’s drug Xeljanz got a 5-year extension in the U.S. because of regulatory delays. In Brazil, the same drug expired on time-no extension. That’s why global pharma teams have lawyers and analysts whose only job is to track these deadlines across 50+ countries.

Maintenance Fees: The Silent Killer

Even if your patent is still within the 20-year window, it can die if you forget to pay. Most countries require maintenance fees-at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years in the U.S. In Europe, you pay annually after the third year. In Mexico, you pay at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years. Switzerland? Just one payment at grant.

Missing a payment doesn’t mean you get a warning. It means your patent expires immediately. No grace period? Not always. The U.S. gives a six-month grace period with a late fee. But in China, if you’re late by even one day, your patent is dead. No exceptions. That’s why companies use automated systems to track these dates. One missed payment can cost millions in lost revenue.

Utility Models: The Short-Term Alternative

Not all patents are created equal. In countries like Germany, China, Japan, and South Korea, you can file a utility model instead. These are simpler, cheaper, and faster to get. But they last only 6 to 10 years. They’re great for mechanical devices, tools, or consumer products that don’t need long-term protection. But they can’t be used for drugs or software in most places.

Some companies use utility models as a stopgap. File a utility model in China for 10 years, then file a full patent in the U.S. for 20. It’s a layered strategy. But if you rely on it too much, you risk losing protection when the shorter term ends.

Regional Systems: The EU’s Unitary Patent

In June 2023, the European Union launched its Unitary Patent system. Now, instead of validating a patent in 17 countries individually, you can get one patent that covers all participating EU members. The term? Still 20 years from filing. But now, you pay one maintenance fee, and it’s enforced in one court. It’s simpler. But it doesn’t change the expiration date. Just the paperwork.

Why This Matters: Real-World Impact

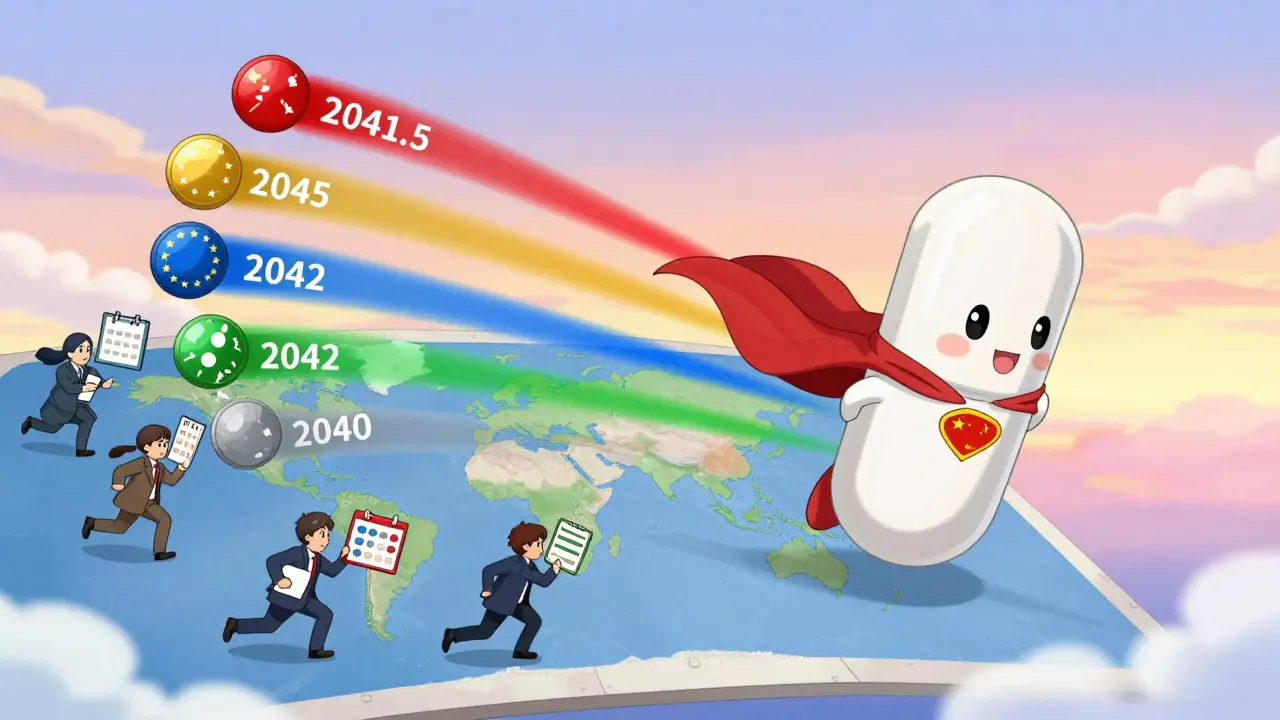

Imagine a new cancer drug. It’s patented in the U.S. on January 1, 2020. The company files in Europe, Japan, and China two months later. The drug gets FDA approval in 2028. But the USPTO took 5 years to approve the patent-so they get 1.5 years of PTA. The EU grants a 5-year SPC because of regulatory delays. China grants a 2-year compensation for examination delays. Brazil has no extensions. And in India, the patent expires on time.

So what’s the real expiration date?

- U.S.: January 1, 2041.5 (20 years + 1.5 years PTA)

- EU: January 1, 2045 (20 years + 5 years SPC)

- Japan: January 1, 2042 (20 years + 2 years extension)

- China: January 1, 2042 (20 years + 2 years compensation)

- Brazil: January 1, 2040

- India: January 1, 2040

That’s five different expiration dates for the same invention. Generic manufacturers in Brazil and India can launch their versions in 2040. In the U.S., they have to wait until 2041. In the EU, they wait until 2045. That’s a five-year revenue gap. And it’s all because of paperwork, delays, and rules.

What’s Next?

The world is still trying to fix these gaps. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) keeps pushing for more alignment, especially for pharmaceuticals. But countries like the U.S. and EU want to protect their innovation. Developing nations want cheaper drugs. No one agrees.

For now, if you’re managing a global patent portfolio, you need more than a calendar. You need a system. A team. A database. Because patent expiration isn’t just about dates. It’s about money, competition, and survival.

Is the patent term always 20 years worldwide?

No. While the TRIPS Agreement set 20 years from filing as the global standard, many countries add extensions for regulatory delays, examination backlogs, or pharmaceutical approvals. Some countries, like Brazil and India, don’t offer extensions at all. Others, like the U.S. and EU, can add up to 5 extra years. Maintenance fees and missed deadlines can also cause early expiration.

Does filing through the PCT extend my patent term?

No. The PCT system only delays the need to file in individual countries-it doesn’t change the start date of your 20-year term. The clock begins on your original filing date, whether it’s a national application or a PCT application. The 30- or 31-month window just gives you time to decide where to go next.

Can I lose my patent even if I’m within the 20-year term?

Yes. If you fail to pay maintenance fees, your patent expires immediately-even if you’re only one day late. Countries like China and Mexico have strict deadlines with no exceptions. In the U.S., you have a six-month grace period with a late fee, but you still must pay. Forgetting one payment can cost millions.

Why do pharmaceutical patents last longer in some countries?

Because drug approval takes years. The U.S., EU, Japan, and Canada allow patent term extensions (PTE or SPCs) to compensate for regulatory delays. These can add up to 5 years, sometimes more with pediatric studies. But only if you apply. Countries like India and Brazil don’t offer these extensions, so patents expire on time, even if the drug wasn’t on the market for most of the term.

What’s the difference between a patent and a utility model?

A utility model is a simplified patent for technical inventions-usually mechanical or physical products. It’s cheaper and faster to get, but lasts only 6 to 10 years. It can’t be used for drugs or software in most countries. Utility models are common in Germany, China, and Japan as a way to protect inventions that don’t need long-term exclusivity.

How do I track patent expirations across countries?

Use a dedicated patent management system that tracks filing dates, PTA, SPC eligibility, maintenance fee deadlines, and national phase entry windows. Many large companies hire specialized teams or use software like Anaqua, PatSnap, or LexisNexis PatentSight. Spreadsheets won’t cut it-too many variables change by jurisdiction.

Do provisional applications affect patent expiration?

No. Provisional applications establish a priority date but don’t count toward the 20-year term. Only non-provisional applications (or PCT applications that enter the national phase) trigger the clock. But if you don’t convert a provisional into a non-provisional within 12 months, you lose the priority date entirely.

Can I extend a patent after it expires?

No. Once a patent expires, protection ends permanently. You can’t renew it. Some companies file new patents on improved versions, but that’s a new invention, not an extension. If you miss a maintenance fee or extension deadline, there’s no way back.

Final Thought

Patent expiration isn’t a single date on a calendar. It’s a living, breathing calculation shaped by bureaucracy, delays, money, and geography. In one country, your drug might be protected for 25 years. In another, it’s public domain in 20. If you’re building a global business around innovation, you can’t afford to guess. You need to know exactly when-and where-your rights end.

11 Comments

Carla McKinney

Let’s be real-the whole system is a rigged casino. Pharma companies exploit PTA and SPCs like it’s their birthright. The 20-year standard? A joke. They file provisional apps years before the drug even works, then stretch it out with bureaucratic loopholes. Meanwhile, patients in India and Brazil pay the price. This isn’t innovation-it’s legal monopolization dressed up as R&D.

Ojus Save

man i read this whole thing and like half of it went over my head but one thing is clear-patents are a mess. why does it matter if a drug expires in 2040 or 2045 if no one can afford it anyway? also typo: ‘experation’ lol

Jack Havard

There’s no such thing as ‘global standard.’ That’s just the PR spin. The TRIPS Agreement was forced on developing nations while the U.S. and EU quietly built their own backdoors-PTA, SPCs, grace periods. This isn’t about fairness. It’s about control. And if you think generic manufacturers in Brazil are just ‘waiting’ until 2040, you’re naive. They’ve already reverse-engineered half the drugs on the market.

Brad Ralph

So the patent system is basically a game of chess where the board changes size every move, and half the players are blindfolded. And we wonder why innovation is slowing down.

Suzette Smith

I get that companies need to recoup costs, but five extra years? That’s like saying, ‘We spent 10 years getting approval, so now we get to lock the market for another half-decade.’ What about the people who can’t afford insulin because of this? It’s not just paperwork-it’s life or death.

Autumn Frankart

Who really benefits from this? Big Pharma? The USPTO? The lawyers? The patent system is a front for wealth transfer. You think the 5-year extension is for ‘regulatory delay’? Nah. It’s for stock buybacks and executive bonuses. Meanwhile, your kid’s asthma inhaler costs $300 because the patent won’t expire until 2045. Wake up.

Pat Mun

Look, I used to work in IP law for a mid-sized biotech firm. I’ve seen the spreadsheets. I’ve seen the teams working 80-hour weeks just to track maintenance fees across 60 jurisdictions. It’s not glamorous. It’s not sexy. But it’s necessary. If you miss a payment in Japan because your intern forgot to update the calendar, you lose millions. And yes, that’s insane. But it’s also how the system works. We need better tools, not just outrage. Maybe AI-driven patent trackers? Or government subsidies for small inventors? There’s a middle ground.

Sophia Nelson

You think this is complicated? Try being a generic drug manufacturer trying to enter the market. You spend $50 million on bioequivalence studies, then find out the original patent was extended by 18 months because the USPTO ‘took too long.’ Meanwhile, the innovator company just filed 17 new patents on minor formulation changes. That’s not innovation. That’s trolling.

Skilken Awe

Let me break this down for you in patent-speak: PCT filing ≠ priority date extension. PTA ≠ patent life extension-it’s a statutory remedy for USPTO delay. SPCs are regulatory compensation instruments under Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 469/2009. And maintenance fees? They’re not ‘fees’-they’re administrative filters to weed out low-value IP. If you can’t afford to pay them, you shouldn’t have filed. End of story.

andres az

Why do you think the U.S. and EU are pushing unitary patents? It’s not to simplify. It’s to consolidate control. Once everything is centralized, they can push for global harmonization-which means killing off countries like India and Brazil that offer cheap generics. This isn’t about patents. It’s about empire-building.

Steve DESTIVELLE

When you think about patent expiration you are thinking about time but time is not linear it is a construct of human perception and the patent system is a mirror of our collective anxiety over ownership and scarcity. We cling to 20 years because we fear the unknown. But what if the real innovation is not in extending patents but in dissolving the illusion that ideas can be owned? The drug is not yours. The molecule is not yours. The knowledge is not yours. It belongs to the universe. We are just temporary custodians. Stop fighting over expiration dates. Start asking why we ever thought we could own a cure.